Beer Styles Series: Maibock or Helles Bock

Monday, April 5th, 2021by Jim Vondracek

Today, we’re taking a deep dive into a seasonal style – the traditional Maibock, now called the Helles Bock in the latest BJCP style guidelines. Seasonal brewing with beers like the Helles Bock can be great fun, as homebrewers establish their own traditions or follow historical patterns that may be hundreds of years old.

History

The Helles Bock fits into a traditional calendar of German bock brewing – the traditional or Dunkel Bock brewed for the winter, the Doppelbock for Lent (to provide sustenance during fasting) or early spring, and the Helles Bock for May and the lead into summer. It fits neatly into a season that is post-doppelbock but pre-autumn festbiers.

The history of the Helles Bock is also tied into the broad movement of German brewing from darker to lighter beers, with the advent and growing popularity of pale malts in the early 19th century.

Before then, German beers, including bocks, were brown or dark. First developed in England, pale malting came about when kilning by burning wood was replaced with coke. The Germans were not quick to embrace the new pale malts – the locals loved their brown beers, including bocks. Using the new pale malts, brewers in Pilsen, Bohemia, developed the pale style that eventually came to rule the world – the Pilsner. Eventually, its popularity led German brewers to adapt, leading to the development of many pale styles we now equate with German lagers – Helles, Festbiers, German Pilsners, Dortmunders and the Helles Bock.

Perhaps not coincidentally, at the same time pale beer arose, the popularity of clear glassware for drinking grew, replacing the ubiquitous pottery, ceramic, metal or wooden drinking tankards. Now those pretty pale beers could be shown off!

For the Helles Bock in particular, it is anecdotally accepted that the style began at Munich’s Hofbrau, starting in the 1600s. At that time, the royal household were not entirely pleased with the offerings from Hofbrau and desired beers brewed in the style being popularized in Einbeck – Bocks. Later, with the advent of the pale malts, Hofbrau made their bock more pale and hoppier, leading to what we now think of as the Maibock or Helles Bock.

Style Characteristics

Today, the Helles Bock is a beer of some strength, generally pale ranging from golden to a light amber. As a style, it can be thought of as sitting between the Dunkels Bock and the Munich Helles or Festbier. It is a big, strong malty lager like the Dunkels Bock, but paler and with less rich malt character and more balanced, by bitterness and dryness. Compared to the Helles or Festbiers, it is maltier and stronger.

Maltiness is moderate to strong in this style, both in aroma and flavor. It can have some Maillard-type character, but shouldn’t be caramelly or have any dark fruit character, unlike the Dunkels Bock. While still malt-forward, it gives the perception of more balance than the traditional bock because of its well-attenuated nature and elevated bitterness.

Like most lagers, it has a ‘clean’ fermentation character, without perceivable esters or phenolics. Some fruitiness from Munich malt is sometimes present in this style, but that isn’t from fermentation, whose character should be clean.

In addition to a clean fermentation, this style depends upon a fuller attenuated fermentation than the traditional bock. This should not be a sweet beer, but have a mostly dry finish.

Mouthfeel is important for the style. It needs a medium body to impart a sense of fullness that is a part of our enjoyment of bocks. It also needs to have solid carbonation, up to medium high carbonation – this carbonation couples with the attenuation and bitterness to make this a more ‘drinkable’ version of the bock. A light alcohol warming also enhances our enjoyment of this style – but it should never be hot or fusel.

The Numbers

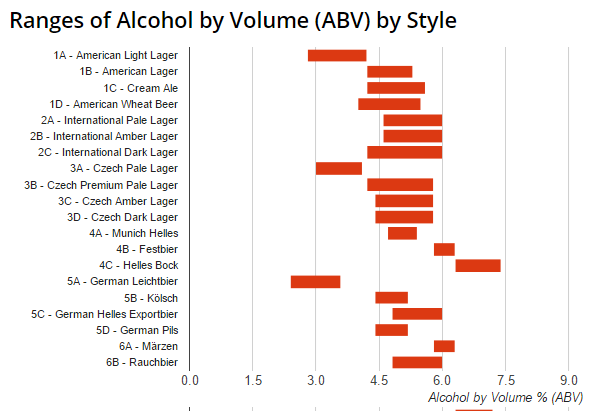

- According to the BJCP style guidelines, the Helles Bock comes in at:

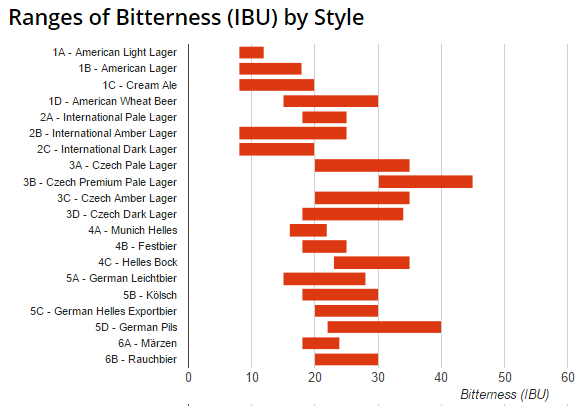

- Bitterness 25-35 IBUs

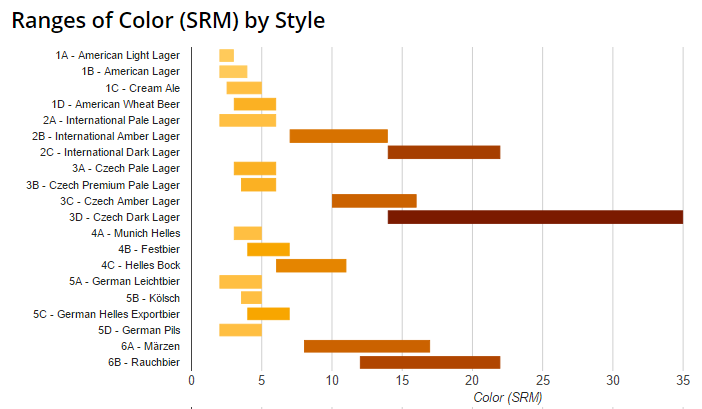

- Color 6-11 SRM

- Original Gravity 1.064 – 1.072

- Final Gravity 1.011 – 1.018

- ABV 6.3% – 7.4%

Brewing the Helles Bock

As with all German lagers, any discussion of the Helles Bock soon becomes a conversation about whether to decoct or not. The bottom-line is that people make an excellent Helles Bock both ways. One way to approach it is as an interesting experiment – perhaps do a simple version of a decoction, a single decoction, and see how challenging you find it for your brewing process and set up. Or if you’re already an experienced decoction brewer, do a three or four decoction mash and see how much complexity you can pull out of the simple grain bill.

Without a decoction mash, some brewers use melanoidin malt to mimic the flavors produced by decoction. If you do this, show restraint, too much melanoidin can make the beer sweet and too dark for this style – Brewer’s Friend can help you track the color and the percentage, which should be no more than 5% of the grain bill.

Otherwise, specialty grains are generally not used in the Helles Bock. Brewers adjust the percentages of three base grains, typically – Pilsner, Munich and Vienna – to get the flavor, aroma and color profile they are looking for.

While still malt forward, the Helles Bock does need a firmer bitterness than the traditional bock. Hops are usually German noble hops, often Hallertau Mittelfruh, although you can certainly use hops from other areas whose parentage traces from the noble hop category – like American-grown Liberty, Mt. Hood or Sterling.

As with all lagers, yeast and fermentation are critical to the Helles Bock. Choose a clean, well-attenuating and flocculating yeast that will enhance malt character. White Labs Bock Lager and Southern German Lager strains are good choices. Omega’s Bock Lager and Wyeast’s Munich Lager and Hella Bock strains are also excellent choices. Dry yeast options are also available – Lallemande’s Lalbrew Diamond and Fermentis’ Saflager W-34/70.

Pitching sufficient amounts of healthy yeast is important to producing clean, well-attenuated lagers. Generally, pitch rates for lagers are higher than for ales, and because the Helles Bock is a bigger beer, it needs an even higher pitch rate. Use the pitching calculator at Brewer’s Friend to make sure you’re pitching enough yeast.

You can pitch multiple packs of yeast, but that can get expensive fast. You can also make a starter, for a beer like the Helles Bock, it will need to be a big starter and probably will need to be stepped up twice. For beers like this, I will sometimes do a three-gallon extract batch with no hops, pitch two packs of lager yeast, let it ferment out for ten to twelve days at 50F, then pour off the ‘beer’ and pitch the remaining yeast cake into the lager. For me, this is often easier than a multiple step starter that ends up still not being big enough.

Generally, lagers require fermentation temperature control. Standard practice is to ferment at 50F. My practice is to chill wort to below 50F, pitch the yeast, let it rise to 50F and then ferment there for ten to twelve days, finally raising the temp to 65F. This can serve as a diacetyl rest, although I find that if I pitch sufficient amounts of healthy yeast at the right temps, diacetyl is usually not a problem. But raising the temp does encourage the yeast to finish up their job and get the final bit of attenuation

After fermentation, I drop the temperature to 34F and lager it for at least two weeks. I carb at that temperature, too, and storing it in a cold keg in a fridge or keezer is also like lagering, so often the beer will have lagered for about a month before getting served.

Helles Bock Recipe

View the recipe in Brewer’s Friend here.

- OG 1.069

- Bitterness 31 IBU

- Color 7 SRM

- Final Gravity 1.014

Grain Bill

8 lbs Pilsner

5 lbs Vienna

3 lbs Munich

Mash

Double Decoction, steps at 142F, 152F and 158F

Batch Sparge

Water – Chicago municipal water (Lake Michigan), target mash pH 5.3, with 13 ml of lactic acid

Hop Schedule

2 oz Hallertau Mittelfruh 3.7AA @ 60 minutes

1 oz Hallertau Mittelfruh @ 30 minutes

1 oz Hallertau Mittelfruh @10 minutes

Yeast

Omega Bock Lager or other yeasts mentioned above

Other

Whirlfloc added with ten minutes left in the boil, White Labs Clarity Ferm pitched with the yeast

Commercial Helles Bocks – On Tour’s Low Boy

As a style, the Helles Bock hasn’t been as commercially popular here among craft beer brewers, compared to the traditional Dunkels Bock or even the Doppelbock. The most popular commercial Maibock in this country isn’t a lager – its Rogue’s Dead Guy, which Rogue describes as a Maibock Ale. Compared to its German counterparts, Dead Guy has more toffee and caramel aromas and flavors. That being said, its both popular and award-winning.

One of my favorite German Maibocks is from Ayinger. I’ve never had it fresh, from the source, but the imported bottles I’ve had have been delicious.

I’m also fortunate to live near a brewery here in Chicago that won a Gold Medal at the Great American Beer Festival for their Maibock – On Tour’s Low Boy. Like the best examples, it has a high drinkability factor, because of its balance, carbonation, smoothness – you don’t realize you’re drinking a beer that is quite as big as it is.

A group of us spoke with Dave Campbell, brewer at On Tour, at a Helles Bock tasting featuring Low Boy. Some highlights from that conversation include:

- Grain Bill – in addition to Pilsner and Munich, On Tour uses rye malt in Low Boy, along with melanoidin, cara-amber, and a touch of caramel malt

- Water – On Tour uses Lake Michigan water, and does small adjustments with calcium chloride, calcium sulfite, and phosphoric acid

- Hops – Columbus for bittering and Czech Saaz at the end, in the last ten minutes

- Yeast – BSI Andechs strain, originally from a monastery brewery outside Munich, 72% attenuation and strong flocculation

- Fermentation – starts at 53F, let rise to 55F over the first couple of days, halfway through fermentation raise it to 60, then slowly drop to lagering temps; four weeks total for fermentation and lagering

According to Campbell, On Tour brews Low Boy seasonally, in late winter, to be served in the spring. It’s a beer they are known for, because of the medal, but he called it a “taproom hero”, meaning that people come to the taproom for a ten ounce pour, but then switch to drinking their popular and more crushable IPAs and other offerings.

Whether drinking a commercial offering like Low Boy or your own handcrafted Helles Bock, enjoy this sure sign of spring as we leave the doldrums of winter. Prost!